Singapore is betting on Chips, again

Can Singapore reclaim its position in the chip-making industry?

Hi Disruptors 👋,

This is the second issue of the week, I want to talk about something that is close to my heart, Singapore’s semiconductor industry. I care about Singapore & SEA because I am based here. The semiconductor is a crucial building block of Singapore’s economy.

I have a comprehensive explanation of the semiconductor industry coming up in the next few letters, stay tuned!

The last letter on Hydrogen energy performed great with a 51% open rate, which means over half of you guys opened up Disrupted and read my analysis on Hydrogen energy. Thank you for that!

Singapore is betting on Chips, again

This is the most recent Mckinsey analysis ranking corporate profits by industry. One should care about it because it gives one an idea of which industry is more promising in the future. As you can see, tech firms and software companies remain top of the list making the most profits, along with pharmaceutical companies. But what genuinely surprised me is the industry that is number one on the list, semiconductors. I don’t think I need to remind this audience how incredibly sensitive the topic of semiconductors has become in recent years, but below is a testament to its importance going forward.

McKinsey calls it “The Great Acceleration”.

The best industries are getting better, and the worst are getting worse.

What’s counterintuitive, for example, is that the banks are among the worst-performing industries in the past years. From a society’s perspective, banks were never meant to be an industry that can support millions of jobs, it is an elite industry for the few. But it is important for the rest of us to see the shift back to high-end manufacturing and industries and understand what the future has in store for us.

This understanding is even more critical for a country, and that’s what I want to explore today.

I want to explore a country’s action towards this shift, the reemergence of the semiconductor industry. And that country is Singapore.

Early Days, Singapore looking for its identity

Before the idea of entrepreneurship was popularized over the past decades by the stories of Google and Amazon. There were 4 major disruptors on the world stage, competing at a national level. These were the four Asian tigers including Singapore, Taiwan, South Korea & Hong Kong, each had its unique advantages, but all of them fulfilling the same demand from the post-WWII western bloc, the need for cheap, disciplined & skilled labor, and an alternative to the rise of Japan.

At that time, the world was divided into two camps, the USSR-led communist bloc, and the US-led western bloc. Unless you’re in the communist bloc in eastern Europe, most economic demand, if not all, came from the US and Western Europe. Therefore, for the four Asian Tigers, producing and selling products to the U.S. was the only path to prosperity.

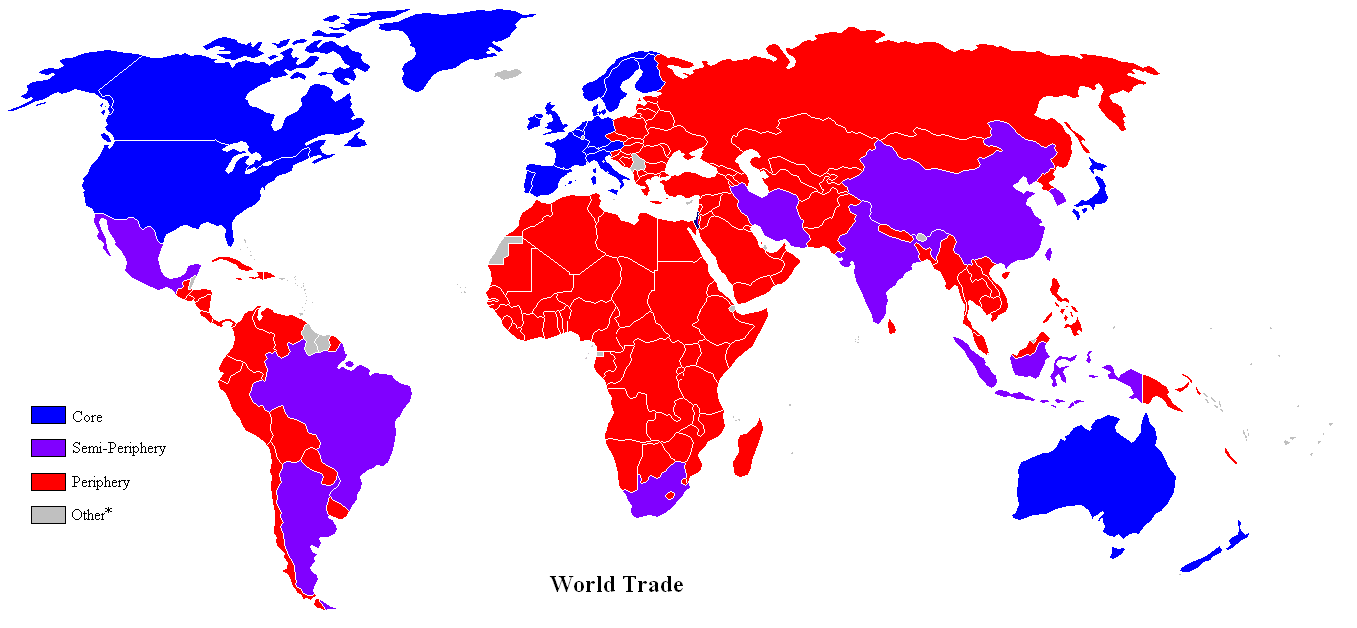

I wanna briefly mention an economic theory called a core-periphery theory by Immanuel Wallerstein, which classifies our world into three camps of countries, core countries like the U.S., semi-periphery countries like China, and periphery countries like Russia.

He argues that the core countries like the U.S. and EU dominate the means of production (technology and capital) and the demand for consumption; semi-periphery countries are manufacturers and producers of products sold to the core countries, the periphery countries are the suppliers of resources such as minerals and oil. He argues that the system is exploitative towards the periphery countries, therefore, it is every country’s job to move from the periphery to the core. This essentially explains why countries like the U.S. could print greenbacks to keep their economy going, it is a privilege for the core countries.

Under this theory, in the 60s and 70s, Singapore’s case was the worst. Being an island nation with a majority Chinese, not only did it lack any resources to sell, it was surrounded by Muslim nations who are not exactly friendly to her.

It was Singapore’s job to tackle this impossible adversity and make herself relevant for the demand from the U.S. and EU. By attracting MNCs to set up shop in Singapore, including some of the biggest electronics companies and oil companies, Singapore quickly industrialized and become a core node to the world’s trade and finance. Thank god for its location at the busiest sea route in the Malaca strait.

(Side note: China’s rise followed the same path. The only difference is that China is now the biggest consumption market for products, this gives China significant leverage in the global economy even under tremendous pressure from the U.S.)

To make itself relevant, in 1961, Singapore’s Economic Development Board (EDB) was set up to attract foreign investors into Singapore. They were essentially evangelists for Singapore’s economy, going around the world pitching Singapore to MNC executives who are looking to increase their profits. The great selling points of Singapore were its disciplined, efficient, and well-trained labor, its tax incentives for MNCs, and its location as a critical sea hub.

Back then, in the context of decolonization, Singapore’s had a lonely path. It’s hard for us to understand now because everyone wants a Microsoft or an Amazon presence in their country, but for governments in the 60s, western companies were seen as imperialist stooges setting up shops in developing countries to extract local resources, ignoring the management expertise and training available to the locals in the process.

Singapore’s lack of choices became its strength.

By 1980, Singapore and the four Asian tigers’ success has caught people’s attention, it has attracted companies like Intel, Apple, IBM, Exxon mobile, and so on to invest in local industries and they made tons of money.

During the last 4 decades of the 20th century, Singapore’s economic growth was at an average of 6%, 10%, 7.3%, and 8% per year, pushing it past developed country status.

The Journey of making Chips begins

After many years of building electronic devices for IBM and Intel.

In 1987, Singapore’s Chartered Semiconductor manufacturing was established, funded by ST engineering, which is fully owned by Temasek, a sovereign wealth fund. It was a great initiative. Founded in the same year as TSMC, CSM became a formidable player in the foundry business.

It is important to note that the foundry model was a bold approach to a new era. Most companies in the chips industry up until 1990 were integrated device manufacturers (IDM), they do everything themselves, from design to manufacturing to testing. CSM and TSMC were the first few companies who saw the potential in specializing in chip fabrication and launched their whole business on this idea. They were right. The foundry + fabless model created a new breed of fabless chip designers like Qualcomm and NVidea who specialized in chip design.

By the year 2004, Singapore had claimed two positions in the top 10 chips foundries. CSM is behind only TSMC and UMC, Singapore’s SSMC was also the number 6 on the list.

Three out of the four ‘Asian tigers benefitted from this semiconductor boom. Samsung of South Korea, TSMC of Taiwan, and CSM of Singapore.

But here is the unspoken rule of the industry. Gradual migration of labor-intensive fabrication out from the US to Asia is ok, but the U.S. must keep the capital-intensive and highly profitable segment within the US. This shaped the current landscape of the chips industry as seen below.

The U.S. dominates the high-profit, capital-intensive design segment of the semiconductor supply chain, and the four Asian tigers were to focus on the labor-intensive fabrication segment.

The EDA tools and IPs needed for chip design, and equipment needed for fabrication are all mostly made in the U.S. The most powerful chip designers like Qualcomm, Apple, Nvidia, AMD, and Intel, you name it, are all based in the US as well.

But only if it is that simple.

The miscalculation of the U.S. companies was that they didn’t expect how important fabrication was going to be in the semiconductor industry. It turns out, as chips got smaller, designing the chip isn’t the hardest part, fabrication is. Huawei of China, through R&D, is now able to design chips that rival Apple, but it will take another 5 years for any Chinese company to catch up with TSMC in the cutting edge 5nm chip fabrication.

This is why everyone is talking about “chokepoints’ in the semiconductor industry nowadays, fabless designers aren’t the choke points, fabrication plants are.

This led to VP Kamala Harris' speech in Singapore a week ago. She said to a group of executives in Singapore that

securing a semiconductor and overall electronics supply chain has become a national priority [for the US]

She was referring to American national champions’ manufacturing plants in Singapore, GlobalFoundries (GF), and Micron. As Singapore plays a more critical role in the U.S. national security for chips production, Singapore will be a more important node in the semiconductor supply chain going forward.

Getting a little bit more technical, GF Singapore is focused on products with 40nm node and above, and Micron’s products in Singapore are from 20nm and above focused on memory products.

How is it different this time?

Geopolitics. The U.S. holds many advantages over the Chinese and the U.S. is anxious about Taiwan’s dominance over the cutting edge <7nm nodes. Unlike other regions in the U.S. semiconductor supply chain, the U.S. does not have military bases in Taiwan. On top of that, China sees Taiwan as its renegade province.

This will not mean a migration of Taiwan’s semiconductor business to Singapore, I am not predicting that. But this will mean more volatility in the business and more American semiconductor investment in Singapore.

Further, our current focus on cutting edge chips with more and more transistors per processor is fueled by smartphones, and the future of chips isn’t just about smartphones, it’s about cars, 5G equipment, cloud applications and etc. These applications are not constrained by the size of chips. The truth is, they do not care if a chip is the size of our fingernails, they care about the design of chips, and whether they can run the AI algorithms more efficiently.

TSMC may be the best at the cutting edge semiconductors of less than 7 nm, it’s not dominant in other node specifications. Chinese company’s current bid to acquire Newport Wafer Fab (NEF) in South Wales shows exactly that. If you take a look at NWF’s node size, its capability is in the 180nm and above category, focused on the auto applications.

This is Singapore’s second shot at semiconductors, at least to the American semiconductor supply chain, competing on the higher node size category.

CSM was one of the world’s most powerful semiconductor fabs in 2004, but it was sold to GlobalFoundries in 2009, effectively exiting the semiconductor market for Singapore.

Though that ends Singapore’s ownership of Semiconductor companies, Singapore’s stake in the chips supplier chain did not diminish. GlobalFoundries made CSM even greater than before. In 2020, GF has one-third of its employees hired in Singapore providing thousands of high-tech jobs for Singapore’s economy and in July 2021, GF announced a 4 billion dollars commitment to expands its production in Singapore. This will enable Singapore to become an important node in the semiconductor supply chain.

As seen above, no one other than TSMC and Samsung is able to support huge investment into 5nm chip R&D. Over the decades of consolidation in the semiconductors market, companies in Singapore have exited the cutting edge fight between Samsung, Intel, and TSMC. Right now, TSMC dominates the below-10nm chip capacity with over 92% of the market share, it is in a different league.

And with GlobalFoundries in Singapore focuses on >40 nm process nodes and Micron focus on 20 and above, this is now the new area for competition, because the applications in the next decades will be more diverse than this decade, and the size constrain will be less important. (Think auto, 5G equipment, Cloud equipment).

Since China and Taiwan take over 50% of the >45 nm fabrication market, GF’s Singapore plant is critical for the U.S. competition with China over this vertical, making sure that China will not be able to establish its own chokepoints for U.S. auto production.

So what should Singapore’s semiconductor strategy be?

Here are some of my thoughts. (If you’re a decision-maker in this field, I am happy to have a chat with you on this, especially if you’re based in Singapore.)

Singapore should have a national strategy specializing in one or a few chips vertical(s). Chips production is R&D intensive and CapEx intensive, this has led to consolidation in the fabrication business, company gets more and more specialized over time with more M&A activities.

Encourage Fabless startups to innovate in future applications. Many Chips verticals are opening new opportunities, traditional logic chips focused on computing, and graphics no longer suits all demands in other applications like cloud, AI, and auto. More specialized chip design is necessary for specialized chips usage.

Government-led investment into key Fabless & Foundries worldwide. Singapore government has a strong track record of strategic investments, led by Temasek and GIC. Singapore should aim to invest in semiconductor companies based on their strategic importance as well as their relevance to Singapore’s future. (Side note: generally, investment in semiconductors is highly desirable as the industry is expected to rise in the next decades fuel by the boom in its applications)

Constantly help local champions like GF and Micron to develop more sophisticated & specialized technology based on Singapore’s semiconductor strategy.

The decision to have a closer tie with U.S. companies needs to be managed carefully, Singapore should be sensitive towards geopolitics, striking a balance between U.S. and China.

Great analysis as always. I really like how you put it all in to historical context! Keep up the good work!

I prefer to read your articles directly in Gmail, does that not count in your "open rate"?